From riksdaler to kronor

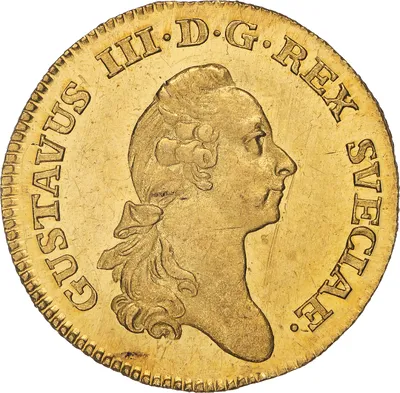

The display case shows a selection of the coins and banknotes issued during the period 1777-1873. The period began with the introduction of King Gustav III’s so-called coin realisation, currency reform, which was decided in 1776. The currency reform meant that the riksdaler, made of silver, became the main coin. It was divided into 48 skillings, which were made of copper. However, the skilling coins only began to be minted in 1802; before that, öre silver coins and öre copper coins were minted, both made of copper. 2 öre silver coins, or 6 öre copper coins, were equivalent to 1 skilling.

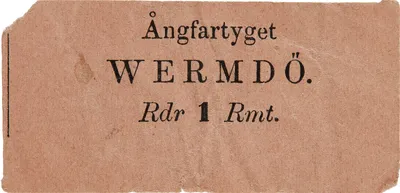

Because Gustav III had few copper coins minted, there was a shortage of credit money, i.e. coins where the metal is worth less than the denomination of the coin. For this reason, tokens minted for Stora Kopparbergs Bergslag began to circulate outside the Bergslag trading area and were valid as coins throughout Sweden. These tokens are called coin tokens.

The National Debt Office and parallel banknote issuance

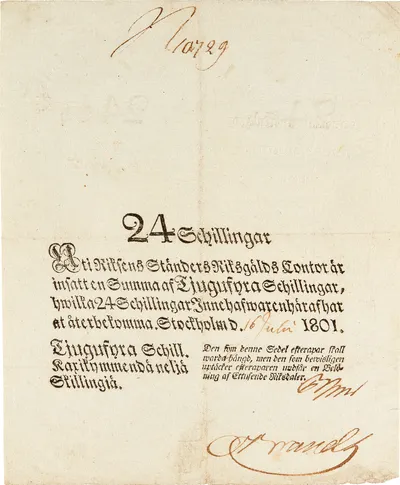

The Swedish National Debt Office was established in 1789 to create order in the state’s finances. When Gustav III started a war with Russia, a lot of money was needed, but the king had promised not to force Ständernas bank, the predecessor of the Central Bank of Sweden, to print new banknotes. Instead, the National Debt Office was left to issue national debt notes. These circulated in parallel with the banknotes from the Ständernas bank, initially at the same value. But the National Debt Office issued so many notes that they fell victim to inflation. The value of the National Debt Office banknotes fell, and the ordinary banknotes were forced out of circulation. It wasn’t until 1836 that the last national debt notes were withdrawn and they were abolished completely in 1846.

Swedish kronor

In 1855, the coinage was changed again, when the decimal system was introduced. The main coin became the riksdaler riksmynt, which was divided into 100 öre. In connection with this, copper coins disappeared and were replaced by bronze coins. In 1873, the coin reform was carried out that resulted in the current coinage system in Sweden, where the main coin is the krona, which is divided into 100 öre. At the same time, a coinage union was established with Denmark and two years later also with Norway – the Scandinavian Monetary Union. When the new coinage system was introduced, the main coin was 10 kronor in gold and each 10-krona coin was to contain 1/248 kilograms of fine gold. The highest krona denomination was 20 kronor in gold and the lowest öre denomination was 1 öre in bronze.

Banknote developments in the 19th century

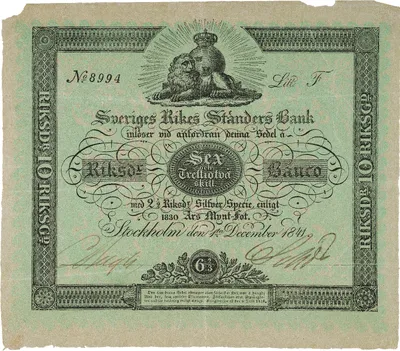

Swedish banknotes improved drastically during the 19th century. Everything from paper to printing techniques changed, as did the colouring. At the beginning of the century, nothing differed from the 1700s. The paper was relatively simple and single-coloured. Printing was carried out using the so-called letterpress technique, or letterpress with types (stamps) made of wood or lead. The security of the banknotes lay mainly in the watermark and the signatures of the bank officials, combined with the threat of severe penalties.

At the Riksbank’s own paper mill in Tumba, a new banknote paper was developed consisting of three layers, the middle of which was coloured depending on the denomination it was to be used for. At the same time, new printing technology was introduced in the form of so-called gravure printing, or copperplate printing. The first banknotes of this new type were introduced in 1835. At first, the banknotes were printed in black only, but in the second half of the 19th century more and more colours were used.

Sveriges Rikes Ständers Bank, the central bank of Sweden, changed its name in 1866 in connection with the parliamentary reform that introduced the bicameral parliament. Even before that, it was common to refer to the bank colloquially as “the Riksbank”, and despite some opposition, the Riksdag decided that the bank should be called Sveriges Riksbank.

Banknotes issued by private banks

A peculiarity of Sweden’s financial life in the 19th century was the many private banks and their banknote issues. The Riksbank found it difficult to reach the whole country and initially welcomed the private initiatives. At most, banknotes from around fifteen banks were in circulation at the same time as the Riksbank’s own banknotes. This was an advantage for the Riksbank, as the private banks bore the entire risk themselves if something went wrong with their operations.

The Riksbank did not have a monopoly on banknote issuance until 1904 and at the same time ceased to compete with the commercial banks in terms of lending and deposits to the public. With a new Sveriges Riksbank Act in 1897, the Riksbank became a central bank in the modern sense, i.e. its customers were banks and financial institutions or equivalent – not private individuals.

1 dukat, Stockholm, Stockholm, Gustav III, 1781

1 dukat, Stockholm, Gustav IV Adolf, 1796

1 dukat, Stockholm, Karl XIII, 1810

2 dukat, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1843

4 dukat, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1846

1 dukat, Stockholm, Karl XV, 1868

1 carolin, Stockholm, Karl XV, 1868

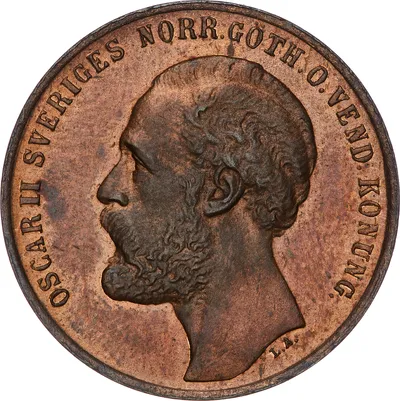

20 kronor, Stockholm, Oscar II, 1873

10 kronor, Stockholm, Oscar II, 1873

1 riksdaler, Stockholm, Gustav III, 1777

1/3 riksdaler, Stockholm, Gustav III, 1777

1/12 riksdaler, Stockholm, Gustav III, 1777

1/24 riksdaler, Stockholm, Gustav III, 1777

1/3 riksdaler, Stockholm, Gustav III, 1778

2/3 riksdaler, Stockholm, Gustav III, 1779

1/6 riksdaler, Stockholm, Gustav III, 1783

1 riksdaler, Stockholm, Gustav IV Adolf, 1801

1/24 riksdaler, Stockholm, Karl XIII, 1811

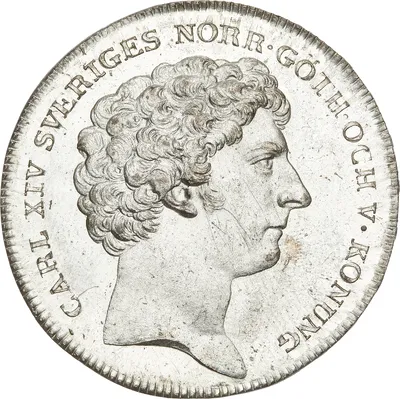

1 riksdaler, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1820

1/12 riksdaler specie, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1832

1/4 riksdaler specie, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1832

1/2 riksdaler specie, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1836

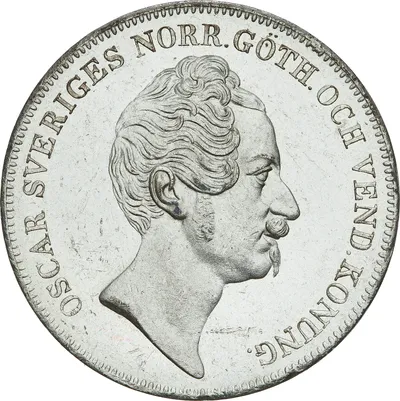

1/32 riksdaler specie, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1851

1/16 riksdaler specie, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1852

1/8 riksdaler specie, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1852

1 riksdaler specie, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1853

4 riksdaler riksmynt, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1856

50 öre riksmynt, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1857

10 öre, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1857

2 riksdaler riksmynt, Stockholm, Karl XV, 1862

25 öre, Stockholm, Karl XV, 1862

1 riksdaler riksmynt, Stockholm, Karl XV, 1867

1 riksdaler riksmynt, Stockholm, Oscar II, 1873

2 öre silvermynt, Avesta, Gustav III, 1777

1 öre silvermynt, Avesta, Gustav III, 1778

1 öre kopparmynt, Avesta, Gustav III, 1778

1/4 skilling riksgälds, Avesta, Gustav IV Adolf, 1799

1/2 skilling riksgälds, Avesta, Gustav IV Adolf, 1801

1/12 skilling, Avesta, Gustav IV Adolf, 1802

1 skilling, Stockholm, Gustav IV Adolf, 1805

1/4 skilling, Avesta, Gustav IV Adolf, 1808

1/2 skilling, Avesta, Karl XIII, 1815

1/6 skilling, Avesta, Karl XIV Johan, 1831

1 skilling, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1832

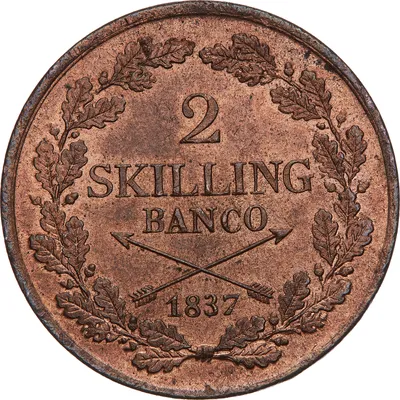

2 skilling banco, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1837

1/3 skilling banco, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1843

1/6 skilling banco, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1839

4 skilling banco, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1852

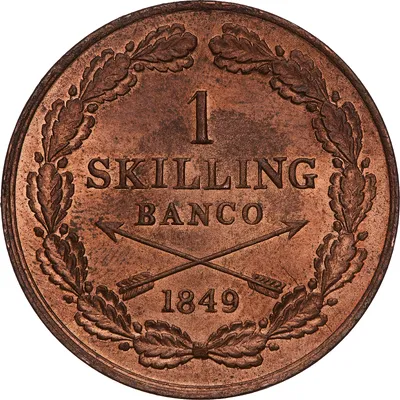

1 skilling banco, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1849

2/3 skilling banco, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1851

1/6 skilling, Stockholm, Karl XIV Johan, 1832

5 öre, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1857

1/2 öre, Stockholm, Oscar I, 1857

2 öre, Stockholm, Karl XV, 1860

2 öre, Stockholm, Oscar II, 1873

5 öre, Stockholm, Oscar II, 1873

1 öre, Stockholm, Oscar II, 1873

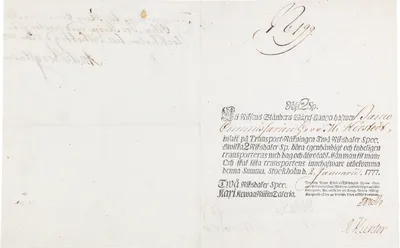

2 riksdaler specie, Sveriges rikes ständers bank, 1777

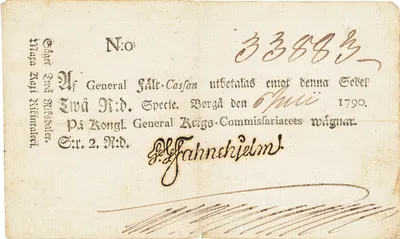

2 riksdaler specie, Kungl. Generalkrigskommisariatet i, 1790

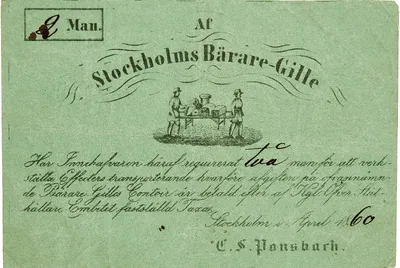

Stockholm, Stockholms Bärare-Gille, 1860-04

25 öre riksmynt, Stockholm, Sabbatsbergs Fattiginrättning, 1858

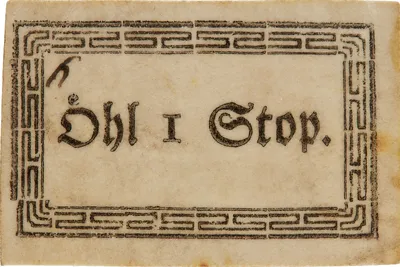

1 stop, Ölsboda, 1890

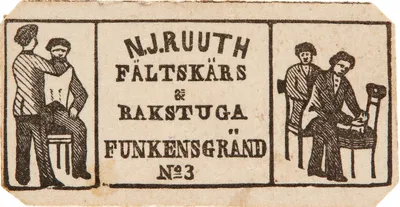

NJ. Ruuth Fältskärs Rakstuga, Funke,

1 riksdaler riksmynt, 1883

24 skillingar riksgälds, Stockholm, Riksgäldskontoret, 1801